Tuesday, November 14, 2006

China - We Don't Censor the Internet ;-)

"A Chinese government official at a United Nations summit in Athens on internet governance has claimed that no Net censorship exists at all in China. The article includes an exchange by a Chinese government official and a BBC reporter over the blocking of the BBC in China."

From the article:

"I don't think we should be using different standards to judge China. In China, we don't have software blocking Internet sites. Sometimes we have trouble accessing them. But that's a different problem. I know that some colleagues listen to the BBC in their offices from the Webcast. And I've heard people say that the BBC is not available in China or that it's blocked. I'm sure I don't know why people say this kind of thing. We do not have restrictions at all."

Two days ago Google Page was blocked. After I wrote an email to Google USA and criticized the ineffectiveness of Google China company, it is OK since yesterday.Google Page has very few Chinese Google fans to use, but the function of uploading of files may has risks.Of course Blogger is totalled blocked, only occasionally when Blogger change its IP or URL it was available. This will help Chinese blog providers to have less pressure to run their business.

Tuesday, September 26, 2006

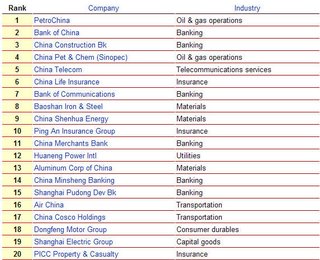

Forbes 40 China

|

This move left China with a lopsided economy, especially its state-owned sector, and has added a unique regional dimension to the restructuring that would anyway be occurring to state-run industries going through the sort of changes that China has been experiencing since Deng Xiaoping set off down the path of economic reform in the late 1970s.

Though it might cause Mao to turn in his grave, private enterprise now accounts for the majority of economic output in China. It is more efficient and faster-growing than the state sector. It is not constrained by being an anchor industrial employer in places where it often has no natural advantages.

Private companies in China remain small--agriculture, wholesale and retail distribution and construction are dominated by thousands of small family firms--and they face considerable barriers to growth; access to markets and capital still depends greatly on connections. They are, though, on the whole profitable.

The state sector, composed of about 150,000 state-owned enterprises, is a different story. These firms are often big and unprofitable. An study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) based on data from 2003 found that they wrung half the productivity from twice the capital.

State enterprise assets represent about 85% of China's gross domestic product, about three times higher than in even the most state-dominated Western European economies, France and Italy, and well above the rate typical in economies making the transition from developing to developed.

Not all are hopeless basket cases. Productivity and profitability are improving surely, if slowly. The return on equity at state industrial firms rose from 3.4% in 1998 to 10.2% in 2003, according to the OECD study. That is short of the private sector's 14.4%, but still passable.

However, the best performance is concentrated in the largest 20% or so of state enterprises. They tend to be the ones that Beijing is using to drive development across the economy in the industries that are the boiler rooms of growth: energy ( PetroChina), banking ( Bank of China), utilities ( Huaneng Power), chemicals ( Sinopec), heavy industry ( Baoshan Iron & Steel), telecommunications ( China Telecom) and transport ( Air China).

Beijing's industrial policy for its state-owned enterprises is two-pronged: to develop national champions that can compete in world markets, and to ease the strain the basket cases impose on the national treasury.

Except at the top end (the companies that make our list of China's largest companies), even China's biggest companies are not so sizable by world standards. Only 14 make the list of the world's 500 largest companies by sales, of which eight are state-owned.

Hence, a policy emphasis on achieving economies of scale and scope. Since the late 1980s, informal links between large enterprises have been formalized through merger and consolidation. That has distilled 120 industrial groups identified as national A-list companies, with a further 2,300 similarly preferred companies at provincial and city levels.

The national champions have been given more decision-making and financial autonomy and priority in the allocation of state-controlled resources, including investment and capital.

They have been encouraged to create research centers (even China's biggest companies devote only 1% of sales to research and development, on average--compared to 5% in the West) and develop their foreign trade. They have also been earmarked for stock-market listings.

They were initially given protective tariff support, although that is being removed in line with China's World Trade Organization entry obligations.

Beijing is also trying to pull off a delicate balancing act: imposing the disciplines of the market on management while keeping policy control of its national and local champions firmly in trusted hands. This has led to the creation of a hybrid group structure, not dissimilar to the industrial groupings that underpinned Japan Inc.

Under this model, a holding company, run by politically appointed managers, controls a network of associated operating companies via controlling or minority shareholdings. One or more of the associated companies may be selected as the vehicle for a public listing on a stock exchange; others of the associated companies may be designated to absorb a large amount of the group's underperforming assets.

A side benefit of this structure is that it has created national industrial networks that circumvent the local protectionism and vested interests that are a legacy of Mao's industrial policy. That, in turn, has eased Beijing's way toward meeting its WTO market-opening obligations.

Since 2003, supervision of the very largest state-owned companies in China has fallen to the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), a high-level commission whose writ runs to about 180 companies. It has set an internal target of having 50 Chinese companies, including state-owned ones, among the largest 500 companies by sales in the world by 2015.

To this end, it recently linked the salaries and bonuses of the presidents of 30 of the biggest state-owned enterprises, including China National Offshore Oil, to the profitability of their companies.

More M&A can be expected in the state sector as China seeks to create more big companies that can compete internationally. Yet perversely, Beijing will try to do this while tightening its hold on the sector rather than loosening it.

Sunday, September 10, 2006

8015 Format Advertisement Wall

Sunday, September 03, 2006

Where do the World's Billionaires live?

China rockin' to "Super Girl"

Hunan: From red state to 'supergirl'

For nearly three hours, Chinese stopped — and voted. No, it wasn't a political revolution, but a mass thumbs up to a 21-year-old from Sichuan who belts out the song "Zombie" from the Irish rock band Cranberries as part of her act.

Zhou Bichang, left, Li Yuchun and Zhang Liangying performed last week during the finals of the "Super Girl" singing contest in China's Hunan province. Li won the "American Idol"-style contest, with 400 million television viewers watching the grand finale. |

China's "Super Girl" is an "American Idol"-style TV show whose grand finale of dancing and singing drew 400 million viewers here Friday night, more than the combined populations of the United States and Britain.

In China, "Super Girl" created a stir from bamboo-forest villages to the crab shacks of Shanghai and is seen as a new phenomenon. Nothing this large and spontaneous has ever pushed its way unapproved into China's mainstream media before.

Some 8 million, mostly younger, Chinese paid the equivalent of 2 cents to send a "text message of support" (the word "vote" is avoided) via cellphone for one of the three Super Girl finalists.

Li Yuchun, a music student whose tomboy looks and confidence onstage are the talk of Chinese chat rooms, won with 3.5 million votes. The three finalists, all in their early 20s, became instant celebrities in a nation that really hasn't made much room for the pop-star concept, except when they come from Hong Kong or Taiwan.

"Super Girl" owes its popularity to its authenticity, to indirectly giving voice to individual Chinese through a vote, and to its unscripted creation of a happy feeling, said a dozen young Chinese interviewed in Beijing Friday.

The program did not, for example, emerge from the Beijing studios of official Chinese programming, but from a provincial station in the gritty heartland of Hunan that has a satellite uplink.

The contest is officially the "Mongolian Cow Sour Yogurt Super Girl Contest." Any female, young or old, talented or not, can participate — not just the beauty-queen types from central casting.

Some 120,000 girls and women took part in the past year, in a sudden and unexpected burst of enthusiasm that has Beijing authorities slightly worried about the precedent it may set for more unregulated forms of pop culture.

"This is totally new to Chinese people," says Wei Feng, a student from the Beijing Foreign Language Institute. "The whole thing is about singing whatever you want, and millions of young girls in those provinces have never had that chance before."

In fact, the two top scorers Friday were "girl next door" types, with the more feminine Zhang Liangying, who sang, "Don't Cry for Me Argentina," coming in a distant third.

Super Girl Li has a small army of young supporters who see her as a role model.

"[Super Girl] represents a victory of the grass-roots over the elite culture," argues Beijing sociologist Li Yinhe.

"It is vulgar and manipulative," intoned an official statement from China Central TV (CCTV), the national state-run broadcaster, which added that the program was not high-toned enough, due to the gaudy clothing worn by contestants, and that the show could be canceled next season due to its "worldliness."

Technically, CCTV officials can shut down "Super Girl," since they hold a monopoly position on broadcast decisions. Many ordinary Chinese say it won't be worldliness that prompts any shutdown, but the fact that CCTV's advertising revenue Friday night was lower than that of its modest Hunan competitor.

A pilot of an official version of "Super Girl" produced by CCTV reportedly failed.

"Most Chinese TV is formulaic," says Luo, a young Beijing University graduate, who would only give his first name. "We can figure out after 15 minutes what will happen, but on "Super Girl" we can't predict what they will say."

Update: Supergirl 2006 show is undergoing.